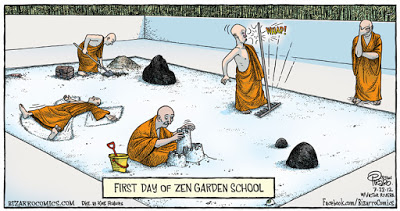

I like to read about meditation – the shelf on my night-table is filled with books by Pema Chodron, Mark Epstein, and various other Buddhist-inspired meditation teachers, whose words and ideas I find soothing, especially before bed. But actually sitting on a cushion and meditating every day? Not so much.

I like to read about meditation – the shelf on my night-table is filled with books by Pema Chodron, Mark Epstein, and various other Buddhist-inspired meditation teachers, whose words and ideas I find soothing, especially before bed. But actually sitting on a cushion and meditating every day? Not so much.

I like meditating in groups, and I’ve enjoyed going to various meditation centers in New York City, which has plenty of them. But I can’t always get myself to a group sitting, and I’ve been especially reluctant this winter.

Meanwhile, I keep seeing new studies studies touting the benefits of meditation – to treat insomnia, reduce stress, improve creativity, even prevent brain shrinkage as we age. So lately I’ve been thinking I really ought to be more serious about doing it.

What I love about the books is learning about Buddhist philosophy and psychology, and its application to daily life. I’ve found the practice of mindfulness incredibly helpful, for example, in getting me to really pay attention to, and appreciate, what I’m doing at any time. I also think it’s invaluable for coaching – encouraging clients to slow down and experience the moment they’re in, or an event or emotion they’re struggling with, has immense benefits and can be really important to the ability to make lasting change.

But I’ve still found it hard to just sit for 20 or 30 or 40 minutes a day with my eyes closed, or staring at the floor, depending on the particular style of meditation involved. I sometimes meditate on the subway, which is always calming, and I’ll practice that kind of one-pointed concentration on the breath or on my movement when I’m running or at the gym or doing yoga, at least for short periods. I even use it to take a nap in the afternoon or fall asleep at night. It’s the sitting still part – and staying awake – that I have trouble with.

I imagine it’s because all my life, I’ve had the feeling that I’m supposed to be doing something – often, something other than what I’m doing. I remember in college, if it was a beautiful day outside and I was in the library studying, I’d feel like I should be doing something outdoors. If I was outside, say, hanging out with friends or going for a run, I would feel like I should be in the library studying.

Now, when I sit down to meditate, that struggle comes up constantly. I immediately think of all the other things I have to do. Within minutes I’ll find myself jumping up and making a to-do list.

I remember being on a weekend meditation retreat once at a retreat center in the picturesque Hudson Valley, and telling the meditation teacher in my interview that I was wondering the whole time why I was sitting on the floor inside all weekend, when I could be outside doing something. He just smiled his wise smile, and told me that was okay, I can just let myself feel that. That sort of helped.

I know it’s in part the way I was raised – in a very traditional, achievement-oriented Jewish immigrant family, where we were always expected to be doing something aimed at achieving some concrete, demonstrable result – studying or practicing the piano, for example. That attitude helped us get into good colleges and graduate schools and landed us professional degrees and accolades, but I think both my brother and I still have a hard time settling down – accepting and appreciating things as they are — just being, as the Buddhists would say. Which is a problem. Because we can’t, and we won’t, always be achieving something. And even if we are, we likely won’t be achieving it as much or as well as we want to, or we’ll be thinking we really ought to be achieving something else.

One of the cornerstones of Buddhism is that life is filled with a “pervasive feeling of unsatisfactoriness,” as the Buddhist psychoanalyst Mark Epstein describes it in his book, Going on Being: Buddhism and the Way of Change, about his own exploration of Buddhism and psychology. “We want what we can’t have and we don’t want what we do have; we want more of what we like and less of what we don’t like.” Seeing this clearly is part of the point of meditation – to illuminate how our minds work and cause us suffering. The idea is that if you see your mind doing this – and as in my retreat, it will start doing this pretty quickly when you sit to meditate – we’re able to recognize those as just thoughts, not necessarily “truths” – and create some space around them, lessening their grip. I understand and appreciate the theory, and it’s helped me become more aware of my thoughts (including the absurd and dysfunctional ones), which has been really helpful. But I still can’t get myself to sit down and meditate every day.

What are other people’s experiences with this? Do you need to have a formal practice of daily sitting meditation to truly incorporate mindfulness and its insights into your life? I’d really like to know.