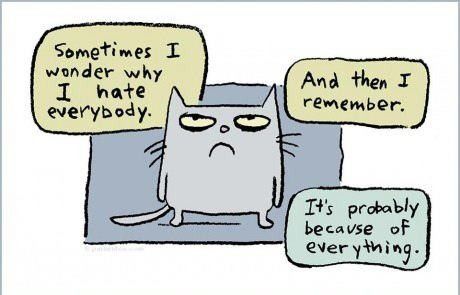

I’ve written almost nothing on this blog since the inauguration of Donald Trump. Partly I think it’s because I’ve been so outwardly focused – fixated on the daily, minute-by-minute news of the disturbing, twisted, often absurd machinations of this new administration that I haven’t taken the time to stop and think much. When I have, usually because all my anger and frustration has exhausted me, what surfaces is primarily a sense of defeat, resignation, and depression.

I’ve written almost nothing on this blog since the inauguration of Donald Trump. Partly I think it’s because I’ve been so outwardly focused – fixated on the daily, minute-by-minute news of the disturbing, twisted, often absurd machinations of this new administration that I haven’t taken the time to stop and think much. When I have, usually because all my anger and frustration has exhausted me, what surfaces is primarily a sense of defeat, resignation, and depression.

The other reason I’m not writing is because I’ve been seeing the world around me as rapidly deteriorating, so everything else seems trivial. I just haven’t been able to muster the energy to think of something positive or hopeful or encouraging to write about. And nobody needs more bad news to read. There’s plenty of that available already.

Of course, when I do stop to think about it, I’m not actually seeing the world deteriorate. I’m reading, watching and hearing about it. It’s the focus of the news, of my Facebook and Twitter feeds, of ordinary conversation with friends, neighbors and colleagues.

What I’m actually seeing on a day-to-day basis hasn’t changed that much — except maybe the buds bursting up in February or the snowstorms in mid-March, which were definitely disturbing. Still, most of what I’m seeing is exactly the same as what I saw when Barack Obama was president: the same buildings and trees outside my window, the same people and dogs on the street, save for a new baby or puppy that’s recently arrived. My physical and visual world, my own life circumstances, haven’t really changed much.

Of course, lots of other peoples lives have changed, especially if they’re undocumented immigrants or Muslim, and I recognize that I’ve been shielded from the immediate effects of Trump’s policy changes by my relative social privilege.

Still, it’s amazing how much our consciousness and sense of the world and of ourselves in it can change based on what we’re reading, watching or listening to: the material our minds consume. On the one hand, it’s wonderful that we can access news from all over the world in such an up-to-the-minute way and know what our government, for example, is doing. On the other hand, having that option can really take us away from ourselves, what we want and care about, and from doing the things and living our lives in ways consistent with that.

In “Life Without Principle,” Thoreau wrote: “We should treat our minds, that is, ourselves, as innocent and ingenuous children, whose guardians we are, and be careful what objects and what subjects we thrust on their attention.”

As the Buddha taught, what we frequently dwell upon determines the shape of our mind.

Many of us can’t just turn off the news, of course, and I don’t think we should. We need to know what’s happening in our political system, and the real consequences it has for millions of people, and for the entire planet, to even begin to try to change it. But taking time to reconnect with ourselves is also key to staying in touch with what’s important to us and to recognizing our own inner strength and resources, despite the mayhem in the political world. It’s also key to refueling — we need to re-connect with a sense of peace, with joy, with beauty, in order to replenish the energy it takes to continue fighting against these larger forces that threaten to overtake our better natures.

In Harper’s this month, Walter Kirn writes of driving from Western Montana to Las Vegas, without looking at or listening to the news the entire time. He finds it eye-opening, revitalizing, and oddly political: “In a supposedly post-factual time, deep attention to the passing scene is a radical act, reviving one’s sense that the world is real, worth fighting for, and that politics is a material phenomenon, its consequences embedded in things seen.”

I learned recently of the death of an acquaintance, someone I knew slightly but not well, and it struck me that even in our occasional encounters, he had touched me deeply. I remember him as open, kind, gentle and wise — all qualities I admire, and would like to have more of.

We don’t tend to think about it, but we influence other people all the time, through even our most ordinary interactions. Taking time away from the public drama to reconnect with ourselves seems key to understanding that, and to reminding us that we can choose how we relate to the world. And that’s really the only way we can even attempt to leave our best impression on it.